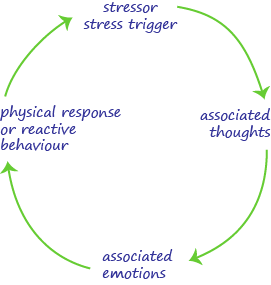

Stress is a part of life. In a life-threatening situation the fight or flight response is appropriate. Any external or internal event, thought or emotion that gives rise to fear or discomfort, can trigger a stress response. We each have varying levels of stress we can comfortably tolerate. If we are habitually exposed to stressors, we may become chronically stressed. Similarly, if we habitually respond to discomfort with a stress reaction, then stress will wreak havoc on our health and well-being. It is all too easy to get caught up in habitual stress patterns that keeps us stuck in limiting beliefs and behaviours. Habitual stress can become a coping mechanism, albeit a negative one.

For example, if I fear confrontation, I may avoid speaking up for myself by becoming stressed in any situation in which I really should speak up for myself. Instead I may tell myself: “Not now, I’m too stressed to deal with this now.” By understanding how stress works we can interrupt the stress cycle. We can change our response by learning how to effectively target our mindfulness practice to break the stress cycle.

The stress cycle has 3 aspects: physical, emotional and mental

- Physically, stress increases tension in the body and the production of adrenaline and cortisol.

- Emotionally, stress increases anxiety and associated feelings such as fear, anger and sadness.

- Mentally, we tend to recycle the same stressful thoughts again and again —that is, we ruminate.

Any single aspect can influence the other aspects. Mental stress will trigger physical and emotional stress. If the mental stress increases, so too will the physical and emotional stress. That is the key thing to understand: if you increase or lower just one aspect, you can increase or lower your overall stress levels. You can reduce the associated mental and emotional stress by physically relaxing your body. As you reduce stress in one aspect, be it physical, emotional or mental, you lower your overall level of stress.

Rumination amplifies your emotional and physical stress levels.

A common trigger for mental stress is a form of thinking called catastrophising and awfulising. This is where we imagine the worst case scenario —what’s the worst that can happen? The more we think like this the more we fuel our physical and emotional stress.

When lost in rumination you can interrupt the stress cycle by moving your attention to whatever you are physically doing —grounding.

You can ground yourself by paying attention to:

- Your breathing,

- your posture,

- a physical sensation,

- or your physical movements, such as working or walking.

It is normal to feel anxiety in anxiety-producing situations.

If you notice that you are ruminating and choose to stop doing it, you can lower your overall level of anxiety. If, on a scale of 0–10, the level of anxiety that “belongs” to the situation is a 4, and your rumination adds another 4, your level of anxiety increases to 8. In that scenario, stepping out of rumination will reduce your level of anxiety back to 4 —a result worth having.

With practice, mindfulness can enable you to respond to stressors from a calmer foundation. I liken it to having a pause button that creates the space in which to choose a response, rather than reacting in habitual ways. It is important to note that stress is caused by an existing stressor. In contrast, anxiety is stress that continues even after the stressor is gone. Anxiety is usually about the future: events that have not yet happened, and may not happen. In mindfulness practice, we commonly ask of our self: “Is there anything I can or need to do now?” —If not we let it be and return to the present moment.

Stress triggers the production of cortisol, a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands, which can become exhausted by chronic stress. Cortisol shuts down our immune cells’ responses and slows digestion and affects the body as a whole. We need to be careful about getting lost in unhelpful memories, especially those we can do nothing about. The key is to step out of rumination and into the present. In the present we can respond to anxiety by asking if there is anything we can or need to do now, and if not, then we let it be and return our attention to the here and now.

Mindfulness Practices: to come out of self-talk, rumination and habitual reactions

Ask yourself:

- How lightly are your feet resting on the floor?

- Do you notice a tingling sensation in the soles of your feet?

- What do your toes feel like, little toe, big toe, all toes?

- Do your feet feel light against the floor or do they feel as though they are rooted?

- Can you feel the tops of your feet?

- How do your ankles feel?

- How do the sensations change?

Now and then, pause and ask yourself: What quality am I bringing to this moment?

The beauty of asking this question is that you don’t have to answer it. By asking the question you take yourself out of the spiral of events and emotions for a moment. In that moment you come into awareness, you notice how you are reacting and you can choose to change your reaction. This is especially useful if your reaction is an old one, drawn from an ingrained pattern of relating to people and events that no longer serves you well.

Ask yourself: What is my mind telling me about this?

The ‘this’ could be your day, a person, an issue, work, the weather or anything. When you ask the question the answer, that comes instantly, can be surprising. You may find that your mind exaggerates some situations and minimises others, complains or is replaying old ideas you thought you had left behind. Ask the question and learn something about the patterns of thinking you fall into. Asking the question can help you to step out of unhelpful reactions.

What we are aiming for, is to be aware of whatever is happening moment by moment —including our thoughts — with a non-reactive attitude. We don’t want to suppress our thoughts, nor do we want to be lost in them. We want to be able to observe them without automatically reacting as though they were always important and always true.